The Radical Infrastructure of Seattle in the 1970′s

Introduction:

In the early 1970′s, a group of people dubbed “the produce section” drove recently harvested grain from radical farms in rural Oregon to the emerging metropolis of Seattle. This grain was taken to a cooperative mill called CC Grains, located near the contemporary Northgate Mall. In an old newsletter, a woman identifying herself only as Gwen wrote the following description:

“I look at CC Grains and I see something wonderful. A place where I could learn and grow non-oppressively. A place where I could dare to challenge my own socialization in a supportive atmosphere. The time, the energy, the tears and hurts, joys and laughter all rolled into a group of women committed to finding another way besides hierarchical, capitalistic, imperialistic ways.”

After the grain was processed, it was distributed through a network of co-operative grocery stores or directly to the kitchens of comrades. Everyone in the network was allowed to purchase everything for exactly 1% above wholesale price. Along with the drivers who brought grain, produce, and dairy products from friendly farms, CC Grains represented material autonomy for the counter-culture of the 1970′s.

In 1970, the New York Times undertook a study in which it found that there were 2,000 communes in the United States that year. Over a dozen of them were near Seattle, and all of their members were plugged into the radical network in the city. During the early 1970′s, the collective spirit was concerned with breaking from capitalism and living in balance with the earth, ideas that shaped the radical infrastructure that grew towards this vision. But as the decade progressed, repression and war took its toll one everyone involved.

The Black Panther Party

During this time period (1968-1978), there was a concurrent network established by the Black Panther Party that focused on feeding and supporting the black community against a violent and racist police force that was often cheered by equally fascistic elements with the population. The group initially established itself in the Central District, Madrona, and Capitol Hill. It’s first headquarters was located at 1127 ½ 34th Avenue, just up the hill from Union and MLK. Three blocks away was the Presbyterian Church where the Party distributed breakfast to 250 children before school every weekday. There were three of these food distribution centers, accompanied by a medical clinic staffed by UW student volunteers, a clothing center, and a free bus that took people to visit their incarcerated family members.

The Seattle chapter of the Party armed themselves to protect their community and infrastructure, following the example of their leaders in Oakland. Against a society that was determined to destroy black people through poverty, drugs, and violence, everyone involved in the Party understood their armament to be a necessary precaution. This proved itself to be true almost immediately.

It started with the morning arrest of two Party members by the SPD. They were accused of stealing two typewriters. Following the arrests, a rally was held at Garfield Highschool on July 30th, 1968.

What followed was a rebellion against the SPD, described here by the Seattle Times:

“A fire bomb thrown at the Special Patrol Squad on the Garfield school grounds about 9:30 PM resulted in a tear-gas dispersal. There was no damage to the landscaping, police said. Tear gas was used at Garfield and also in East Cherry Street at several locations. A flare was used to illuminate the scene as police attempted to clear the playfield. Police reported they routed about 50 youths taking part in making fire bombs behind Garfield Highschool.

“The incident involving the two injured youths occurred at 2608 E. Cherry Street. The [white] man who fired the shots was taken into police custody. The police car in which officer Marquart was injured was fired on 25th Avenue and East Cherry about 9:40 PM. Firemen were summoned to the house about 10:25 when fire bombs were thrown at the building. Damage was slight. Police said three officers assigned to guard the building were fired on at least six times about 3:15 AM.”

This was the climate in which the Party began building its infrastructure. In October of 1968, the SPD killed a young black man and over the months various Party members were arrested on a variety of charges. The Panthers were later evicted from their headquarters and the King County Prosecutor continued to allow the SPD to murder them with impunity, all while the FBI waged its COINTELPRO campaign against the Party. Despite all of this, the breakfast program, the clothing store, and the medical clinics persisted and even outlasted the Party.

Today, the two medical clinics set up by the Panthers are still in the Central District. One is now called the Country Doctor Community Clinic on 19th, the other is the Carolyn Down Family Medical Center on Yesler. Were it not for this infrastructure, there would not have been a history or memory of black militancy in Seattle today.

Black Duck Auto and Leonard Peltier

The rebellion in the Central District in 1968 signaled the opening of a new period of struggle in Seattle. Like the rest of the country, the following years brought repression, drugs, confusion, experimentation, rebellion, shoot-outs, deaths, and moments of freedom to the city. While the Black Panthers were building their own infrastructure, they were accompanied by other allies throughout the city who not only helped fund the Party but built their own networks of supply and distribution. By 1974, there was a large network that included CC Grains, the nearby Little Bread Bakery that used the grain from the mill, co-ops that fed thousands of people, several farms providing the food, Left Bank Books, dozens of collective houses, an auto shop, and over a dozen communes. Each collective project would send representatives to a large spokes-council where the entire network would coordinate.

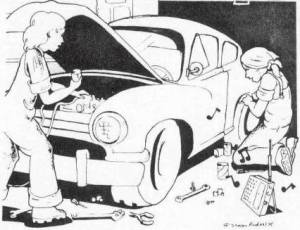

The collective auto shop was started in Capitol Hill in the garage of a house rented by Ed Mead and Roger Lippman. Lippman was a former SDS leader in Seattle who later became affiliated with the local section of the Weather Underground. In 1970, he was sentenced to three months in jail for his role in organizing a protest where the Federal Courthouse in Seattle was vandalized. After he was released, Lippman continued to live in Seattle and eventual found himself living with Ed Mead, a young man from Alaska who had spent most of his life in prison and would go on the help start the George Jackson Brigade guerrilla movement. At their shared house, the two began working on their friends cars on the sidewalk outside their garage. When the number of people needing auto help grew into the hundreds, the men decided to open a proper auto shop called Black Duck Auto.

A flier for the space reads:

“We are a people’s garage, not a capitalist business. We try to relate to you as friends, as well as customers. We depend on the community for support and expect you not to objectify us. (In other words, not relate to us as objects who magically fix your car quietly, quickly, and cheaply without personal or mechanical hassles along the way.) When we work, we take time to do the job right, we explain things to you, work with you if you wish, and enjoy each others company at the garage. It is a learning workshop and a humane environment.”

The auto shop moved out of the house and into a commercial space in Chinatown. On the sly, Roger Lippman and a few others were making fake ID’s for whoever needed one. It is unknown who received these false documents. The garage also serviced vehicles for AIM, the American Indian Movement, and Ed Mead personally equipped an AIM warrior on their way to an armed occupation in 1974. However, when a man named Leonard Peltier arrived seeking fake documents, the forgers in the network turned him down. In anger, Ed Mead moved out of the apartment he shared with Lippman.

Peltier had lived in Seattle for several years after leaving his small reservation town in North Dakota. He took part in the occupation of Fort Lawton in Magnolia where he and dozens of other natives were beaten by police and dragged to jail after trying to take back the land. After this radicalizing experience, Peltier took part in the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs office in Washington, DC in 1972. That November, Peltier was charged with the murder of a Milwaukee police officer. After spending five months in jail, AIM bailed him out just as the occupation of Wounded Knee began in South Dakota. After going underground, Peltier made plans to travel to the occupation but it ended before he could get there.

Officially an outlaw, Peltier returned to Seattle, received a car and weapons, and went off to participate in three more occupations before eventually finding his way to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. It was in this place that a shootout between AIM and the FBI took place, leaving two federal agents and one AIM warrior dead. Leonard Peltier was eventually convicted of murder and sits in prison to this day, the victim of a frame-up that has been extensively documented.

The Co-Ops

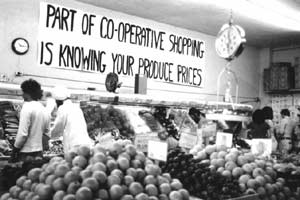

Peltier is one person who was materially supported (or not supported) by the radical infrastructure that existed in Capitol Hill. In his case, the underground network supplied him what he needed, but the above ground network fed thousands of people in Seattle. One of the main nodes of the food network was the Central Co-Operative on 12th and Denny. It began in 1971 as a wholesaler of beans, flour, grains, and cheese, most of it supplied from the farms in the network. Inside there was a lending library and communal stove for warmth and cooking. Anyone could come in at any time and start working.

This network also included the Puget Consumer’s Co-op, or PCC as it is now commonly known. It started as a small network of 200 people who purchased food together and picked it up in a basement depot. By the mid 1970′s, PCC had opened a location in Ravenna and sold food to thousands of people. PCC was part of a growing move towards organic food, inspired by the counter-culture’s desire to escape from the networks of capitalist dependency. While all of these co-ops were blossoming, a boycott against Safeway was also taking place, in solidarity with the United Farmworker’s Movement and against corporate agriculture. The original aim of the co-ops in the radical network was to replace capitalism with a more egalitarian and healthy system built by the people themselves. This vision was pursued by all but when repression landed on the network, things began to change.

The initial FBI offensive against radical movements in Seattle first affected the Black Panthers at the end of the 1960′s and the beginning of the 1970′s. It also affected the predominately white left, although not to the same extent. In 1975, when the George Jackson Brigade (GJB) began its guerrilla campaign against the state and capitalism, the FBI repression intensified against the entire left, either black or white. A Grand Jury was convened in Seattle, jailing one woman for six months and harassing dozens of people in the wider network. Although the vast majority of the GJB attacks did not harm anyone, the radical left in Seattle did not unify in support of the armed group. This caused various splits, leading to Left Bank Books leaving a support coalition for the Grand Jury resistors because of their critical support for the group.

While the FBI pursued the GJB, the co-ops began to move away from their former ideals and focused only on food, money, and new storefronts. PCC began voting about whether to buy sliding glass doors and electronic tellers. Their P-Patch program was adopted by the city and other urban farming projects were given Federal money to expand. Meanwhile, the mental and physical stress of capitalism and repression caused the Central Co-Op to implode in 1978. Most of the volunteers and members of the co-op could not sufficiently discard their former ideals enough to create a “solid business plan” that would allow them to survive in the market.

This was the pattern that emerged after the repression: communes, farms, collective houses, and co-ops began to seal themselves off and become inward focused. No longer was there a vision of a world free from capitalism, instead there was survival, practicality, and money. PCC agreed to help finance the restart of the Central Co-Op only if they agreed to have paid workers and not a collective. Today, the co-op is now called Madison Market. Its benefactor, PCC, exists in ten locations across the Seattle area. Along with similar establishments across the country, these stores are part of what has now become known as green capitalism, the attempted regeneration of a toxic system. There is no more informal 1% above wholesale price for members of the tribe, family, or commune. There is simply a money making enterprise catering mostly to the wealthy.

There are other remnants of this infrastructure in existence today. Some of it exists as part of a network called the Evergreen Land Trust that includes four houses in Seattle and three nearby land projects. One of the collective houses, the Sunset House in the Central District, is well known for its purple exterior. Many of the famous figures in Seattle’s radical left entered the establishment in various ways, some even becoming advisers to the Clinton’s, others becoming local politicians or small business owners. Jeff Dowd, one of the seven people jailed for the vandalism of the Federal Courthouse, went on to become a movie producer. He helped gather the money that financed the creation of Fern Gully: The Last Rainforest, a film that helped shape the minds of the children of the 1990′s.

Capitol Hill

In the late 1960′s and early 1970′s, dozens of collective houses sprung up in Capitol Hill. After the rebellion in the Central District and the loss of 60,000 Boeing jobs between 1969 and 1970, many affluent white people left the neighborhood, causing a drop in rent prices. The counter-culture quickly filled this void, giving Capitol Hill its bohemian reputation. For the first years of the 1970′s, Capitol Hill was a cheap place to live for those hoping to destroy capitalism and build a new world. With them came new ideas, more tolerance, and a desire for experimentation. But soon it was clear that these radicals were unwittingly acting as the vanguard for a force that was just beginning to be understood: gentrification.

Like the punks and squatters of other cities, the radicals of Capitol Hill cleared the way for a new group of people to move in. In a report from 1979, a UW masters student writes: “About 1973, at first gradual, imperceptible—and in many ways quite unusual—changes began. Growing numbers of typically young, white professionals began moving onto deteriorated sections of central and southern Capitol Hill. While Capitol Hill for many years has been the home of people of all income classes, ages, and races, the social composition is now changing towards a young, white, professional, and usually childless resident.”

Following the same pattern as in other cities, the mostly white radicals were able to live normal lives in a neighborhood that other white people found scary or dangerous. Once it was clear that crime rates and dilapidated buildings did not deter new renters, the petty-bourgeoisie began its push to invest and rebuild the neighborhood. With the same “pioneer” spirit that is exhibited today, these small capitalists saw the neighborhood as a cash machine. From the same report:

“In 1973, a very chic restaurant, Boondock’s, opened near the intersection of Broadway and Roy. At the time of its opening the owners were informed by their friends that the location was a bad one because the neighborhood was too poor to support such a restaurant and that they were opening a high-class establishment in the middle of the ‘boondocks,’ hence the name. One of the two owners said of Capitol Hill, ‘It was on the way down,’ but that he was good at ‘sensing trends’ and that after a demographic study of the area they decided it was on the verge of rejuvenation, which would result in the restaurant’s success. ‘The study showed that the white population would come back. And that’s what happened. Professionals, singles, young marrieds [sic].‘”

While this was taking place along the Broadway strip, something more sinister was happening on the other side of the hill near 23rd, in what was then called East Capitol Hill. In the same report, a person identified only as “an elderly black woman” from the Central District explains:

“They gave me a hard time when I tried to move in around here in 1963. Every rooming house turned me down, some even asking if I was a prostitute! Finally I decided to build my own place, and they gave me a hard time downtown with the permit. I ran into a lot of resistance because of my color. The real estate agents are paying to have houses burned down. All my neighbors have been offered enormous sums of money to sell. The whites want this place, but I’ll be damned if they’re going to get it!”

The process of gentrifying the Central district is still underway, although it has met with resistance over the decades. Ever since the rebellion in 1968, there has been an effort to retain the black and working class character of the neighborhood against the tide of gentrification. However, the government sponsored influx of drugs and gangs starting in the 1970′s has severely damaged the Central District and allowed the developers and out-of-town landlords to acquire more property. It also created a justification for racial profiling by the SPD, an organization that has continued to murder, jail, and plant drugs on young black people for decades.

During the last years of the 1970′s, two SPD officers led a campaign to repeal a city ordinance that protected gay rights. The group these cops formed was called SOME, or Save Our Moral Ethics. On Capitol Hill, the radical gay community mobilized against this initiative and in the process revealed some new truths about the neighborhood: firstly, that throughout the decade the gay population had exploded; secondly, many gay people were conservative and just wanted to live a normal capitalist life, in contrast to the radical gays of the neighborhood who wanted to subvert it. The same report quoted above goes on to say:

“Every week or so new graffiti appears on walls on Capitol Hill, sometimes the slogans suggesting it was written by radical lesbians. The pro-gay graffiti is more a sign of efforts to gain a political footing rather than a reflection of actual dominance. The radical gay community on Capitol Hill is numerically small, yet vocal and politically potent. Some of the recent graffiti demands—in no uncertain terms—that the rich leave Capitol Hill immediately, and demonstrates in a graphic fashion growing class conflict in the community. On the other hand, I also interviewed gays who were financially secure and bothered by the growing anti-development sentiment.”

In the 1990′s and 2000′s, the conservative, mainstream gay population began buying and renting property in the Central District, creating more conflict in their wake. Today, the gay identity has been absorbed into capitalism rather than continue to be excluded from. The 1970′s was a time of emancipation and coming out, but it was also a time of mainstreaming and the beginning of the gentrification that continues to this day.

Conclusion

1968 was a year of uprisings across the planet. France, Italy, the US, Mexico, Japan, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Poland, and Brazil were all host to rebellions against the established order. It was the beginning of a period of struggle that would last for nearly a decade and engulf the planet. Some call this time period the Cold War, others call it World War III, and still others call it simply the revolution. It was a global battle that swept up two generations in its complexities and day dreams. Ultimately, the battle was between the USA and the USSR, between state capitalism and state capitalism, but within the cracks of these monolithic entities life was able to blossom.

Two years have elapsed since the Occupy movement arrived in Seattle and it was just a few months ago that police gassed hundreds of people downtown during May Day, 2013. Another network has started to form in Seattle that is just as rhizomatic, nuanced, and informal as the last one. It carries the flame of rebellion within it, raw and new, gathering momentum, constantly growing. Repression has recently swept through the city in various forms and yet the network persists. There is an entire history of struggle to look back on and learn from. This article was written as a contribution to the transmission of those old lessons and a reminder to not repeat mistakes that have already happened.

In the early 1970′s, a group of people dubbed “the produce section” drove recently harvested grain from radical farms in rural Oregon to the emerging metropolis of Seattle. This grain was taken to a cooperative mill called CC Grains, located near the contemporary Northgate Mall. In an old newsletter, a woman identifying herself only as Gwen wrote the following description:

“I look at CC Grains and I see something wonderful. A place where I could learn and grow non-oppressively. A place where I could dare to challenge my own socialization in a supportive atmosphere. The time, the energy, the tears and hurts, joys and laughter all rolled into a group of women committed to finding another way besides hierarchical, capitalistic, imperialistic ways.”

After the grain was processed, it was distributed through a network of co-operative grocery stores or directly to the kitchens of comrades. Everyone in the network was allowed to purchase everything for exactly 1% above wholesale price. Along with the drivers who brought grain, produce, and dairy products from friendly farms, CC Grains represented material autonomy for the counter-culture of the 1970′s.

In 1970, the New York Times undertook a study in which it found that there were 2,000 communes in the United States that year. Over a dozen of them were near Seattle, and all of their members were plugged into the radical network in the city. During the early 1970′s, the collective spirit was concerned with breaking from capitalism and living in balance with the earth, ideas that shaped the radical infrastructure that grew towards this vision. But as the decade progressed, repression and war took its toll one everyone involved.

The Black Panther Party

During this time period (1968-1978), there was a concurrent network established by the Black Panther Party that focused on feeding and supporting the black community against a violent and racist police force that was often cheered by equally fascistic elements with the population. The group initially established itself in the Central District, Madrona, and Capitol Hill. It’s first headquarters was located at 1127 ½ 34th Avenue, just up the hill from Union and MLK. Three blocks away was the Presbyterian Church where the Party distributed breakfast to 250 children before school every weekday. There were three of these food distribution centers, accompanied by a medical clinic staffed by UW student volunteers, a clothing center, and a free bus that took people to visit their incarcerated family members.

The Seattle chapter of the Party armed themselves to protect their community and infrastructure, following the example of their leaders in Oakland. Against a society that was determined to destroy black people through poverty, drugs, and violence, everyone involved in the Party understood their armament to be a necessary precaution. This proved itself to be true almost immediately.

It started with the morning arrest of two Party members by the SPD. They were accused of stealing two typewriters. Following the arrests, a rally was held at Garfield Highschool on July 30th, 1968.

What followed was a rebellion against the SPD, described here by the Seattle Times:

“A fire bomb thrown at the Special Patrol Squad on the Garfield school grounds about 9:30 PM resulted in a tear-gas dispersal. There was no damage to the landscaping, police said. Tear gas was used at Garfield and also in East Cherry Street at several locations. A flare was used to illuminate the scene as police attempted to clear the playfield. Police reported they routed about 50 youths taking part in making fire bombs behind Garfield Highschool.

“The incident involving the two injured youths occurred at 2608 E. Cherry Street. The [white] man who fired the shots was taken into police custody. The police car in which officer Marquart was injured was fired on 25th Avenue and East Cherry about 9:40 PM. Firemen were summoned to the house about 10:25 when fire bombs were thrown at the building. Damage was slight. Police said three officers assigned to guard the building were fired on at least six times about 3:15 AM.”

This was the climate in which the Party began building its infrastructure. In October of 1968, the SPD killed a young black man and over the months various Party members were arrested on a variety of charges. The Panthers were later evicted from their headquarters and the King County Prosecutor continued to allow the SPD to murder them with impunity, all while the FBI waged its COINTELPRO campaign against the Party. Despite all of this, the breakfast program, the clothing store, and the medical clinics persisted and even outlasted the Party.

Today, the two medical clinics set up by the Panthers are still in the Central District. One is now called the Country Doctor Community Clinic on 19th, the other is the Carolyn Down Family Medical Center on Yesler. Were it not for this infrastructure, there would not have been a history or memory of black militancy in Seattle today.

Black Duck Auto and Leonard Peltier

The rebellion in the Central District in 1968 signaled the opening of a new period of struggle in Seattle. Like the rest of the country, the following years brought repression, drugs, confusion, experimentation, rebellion, shoot-outs, deaths, and moments of freedom to the city. While the Black Panthers were building their own infrastructure, they were accompanied by other allies throughout the city who not only helped fund the Party but built their own networks of supply and distribution. By 1974, there was a large network that included CC Grains, the nearby Little Bread Bakery that used the grain from the mill, co-ops that fed thousands of people, several farms providing the food, Left Bank Books, dozens of collective houses, an auto shop, and over a dozen communes. Each collective project would send representatives to a large spokes-council where the entire network would coordinate.

The collective auto shop was started in Capitol Hill in the garage of a house rented by Ed Mead and Roger Lippman. Lippman was a former SDS leader in Seattle who later became affiliated with the local section of the Weather Underground. In 1970, he was sentenced to three months in jail for his role in organizing a protest where the Federal Courthouse in Seattle was vandalized. After he was released, Lippman continued to live in Seattle and eventual found himself living with Ed Mead, a young man from Alaska who had spent most of his life in prison and would go on the help start the George Jackson Brigade guerrilla movement. At their shared house, the two began working on their friends cars on the sidewalk outside their garage. When the number of people needing auto help grew into the hundreds, the men decided to open a proper auto shop called Black Duck Auto.

A flier for the space reads:

“We are a people’s garage, not a capitalist business. We try to relate to you as friends, as well as customers. We depend on the community for support and expect you not to objectify us. (In other words, not relate to us as objects who magically fix your car quietly, quickly, and cheaply without personal or mechanical hassles along the way.) When we work, we take time to do the job right, we explain things to you, work with you if you wish, and enjoy each others company at the garage. It is a learning workshop and a humane environment.”

The auto shop moved out of the house and into a commercial space in Chinatown. On the sly, Roger Lippman and a few others were making fake ID’s for whoever needed one. It is unknown who received these false documents. The garage also serviced vehicles for AIM, the American Indian Movement, and Ed Mead personally equipped an AIM warrior on their way to an armed occupation in 1974. However, when a man named Leonard Peltier arrived seeking fake documents, the forgers in the network turned him down. In anger, Ed Mead moved out of the apartment he shared with Lippman.

Peltier had lived in Seattle for several years after leaving his small reservation town in North Dakota. He took part in the occupation of Fort Lawton in Magnolia where he and dozens of other natives were beaten by police and dragged to jail after trying to take back the land. After this radicalizing experience, Peltier took part in the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs office in Washington, DC in 1972. That November, Peltier was charged with the murder of a Milwaukee police officer. After spending five months in jail, AIM bailed him out just as the occupation of Wounded Knee began in South Dakota. After going underground, Peltier made plans to travel to the occupation but it ended before he could get there.

Officially an outlaw, Peltier returned to Seattle, received a car and weapons, and went off to participate in three more occupations before eventually finding his way to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. It was in this place that a shootout between AIM and the FBI took place, leaving two federal agents and one AIM warrior dead. Leonard Peltier was eventually convicted of murder and sits in prison to this day, the victim of a frame-up that has been extensively documented.

The Co-Ops

Peltier is one person who was materially supported (or not supported) by the radical infrastructure that existed in Capitol Hill. In his case, the underground network supplied him what he needed, but the above ground network fed thousands of people in Seattle. One of the main nodes of the food network was the Central Co-Operative on 12th and Denny. It began in 1971 as a wholesaler of beans, flour, grains, and cheese, most of it supplied from the farms in the network. Inside there was a lending library and communal stove for warmth and cooking. Anyone could come in at any time and start working.

This network also included the Puget Consumer’s Co-op, or PCC as it is now commonly known. It started as a small network of 200 people who purchased food together and picked it up in a basement depot. By the mid 1970′s, PCC had opened a location in Ravenna and sold food to thousands of people. PCC was part of a growing move towards organic food, inspired by the counter-culture’s desire to escape from the networks of capitalist dependency. While all of these co-ops were blossoming, a boycott against Safeway was also taking place, in solidarity with the United Farmworker’s Movement and against corporate agriculture. The original aim of the co-ops in the radical network was to replace capitalism with a more egalitarian and healthy system built by the people themselves. This vision was pursued by all but when repression landed on the network, things began to change.

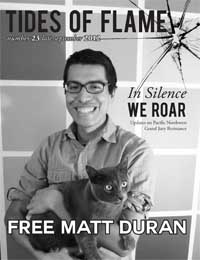

The initial FBI offensive against radical movements in Seattle first affected the Black Panthers at the end of the 1960′s and the beginning of the 1970′s. It also affected the predominately white left, although not to the same extent. In 1975, when the George Jackson Brigade (GJB) began its guerrilla campaign against the state and capitalism, the FBI repression intensified against the entire left, either black or white. A Grand Jury was convened in Seattle, jailing one woman for six months and harassing dozens of people in the wider network. Although the vast majority of the GJB attacks did not harm anyone, the radical left in Seattle did not unify in support of the armed group. This caused various splits, leading to Left Bank Books leaving a support coalition for the Grand Jury resistors because of their critical support for the group.

While the FBI pursued the GJB, the co-ops began to move away from their former ideals and focused only on food, money, and new storefronts. PCC began voting about whether to buy sliding glass doors and electronic tellers. Their P-Patch program was adopted by the city and other urban farming projects were given Federal money to expand. Meanwhile, the mental and physical stress of capitalism and repression caused the Central Co-Op to implode in 1978. Most of the volunteers and members of the co-op could not sufficiently discard their former ideals enough to create a “solid business plan” that would allow them to survive in the market.

This was the pattern that emerged after the repression: communes, farms, collective houses, and co-ops began to seal themselves off and become inward focused. No longer was there a vision of a world free from capitalism, instead there was survival, practicality, and money. PCC agreed to help finance the restart of the Central Co-Op only if they agreed to have paid workers and not a collective. Today, the co-op is now called Madison Market. Its benefactor, PCC, exists in ten locations across the Seattle area. Along with similar establishments across the country, these stores are part of what has now become known as green capitalism, the attempted regeneration of a toxic system. There is no more informal 1% above wholesale price for members of the tribe, family, or commune. There is simply a money making enterprise catering mostly to the wealthy.

There are other remnants of this infrastructure in existence today. Some of it exists as part of a network called the Evergreen Land Trust that includes four houses in Seattle and three nearby land projects. One of the collective houses, the Sunset House in the Central District, is well known for its purple exterior. Many of the famous figures in Seattle’s radical left entered the establishment in various ways, some even becoming advisers to the Clinton’s, others becoming local politicians or small business owners. Jeff Dowd, one of the seven people jailed for the vandalism of the Federal Courthouse, went on to become a movie producer. He helped gather the money that financed the creation of Fern Gully: The Last Rainforest, a film that helped shape the minds of the children of the 1990′s.

Capitol Hill

In the late 1960′s and early 1970′s, dozens of collective houses sprung up in Capitol Hill. After the rebellion in the Central District and the loss of 60,000 Boeing jobs between 1969 and 1970, many affluent white people left the neighborhood, causing a drop in rent prices. The counter-culture quickly filled this void, giving Capitol Hill its bohemian reputation. For the first years of the 1970′s, Capitol Hill was a cheap place to live for those hoping to destroy capitalism and build a new world. With them came new ideas, more tolerance, and a desire for experimentation. But soon it was clear that these radicals were unwittingly acting as the vanguard for a force that was just beginning to be understood: gentrification.

Like the punks and squatters of other cities, the radicals of Capitol Hill cleared the way for a new group of people to move in. In a report from 1979, a UW masters student writes: “About 1973, at first gradual, imperceptible—and in many ways quite unusual—changes began. Growing numbers of typically young, white professionals began moving onto deteriorated sections of central and southern Capitol Hill. While Capitol Hill for many years has been the home of people of all income classes, ages, and races, the social composition is now changing towards a young, white, professional, and usually childless resident.”

Following the same pattern as in other cities, the mostly white radicals were able to live normal lives in a neighborhood that other white people found scary or dangerous. Once it was clear that crime rates and dilapidated buildings did not deter new renters, the petty-bourgeoisie began its push to invest and rebuild the neighborhood. With the same “pioneer” spirit that is exhibited today, these small capitalists saw the neighborhood as a cash machine. From the same report:

“In 1973, a very chic restaurant, Boondock’s, opened near the intersection of Broadway and Roy. At the time of its opening the owners were informed by their friends that the location was a bad one because the neighborhood was too poor to support such a restaurant and that they were opening a high-class establishment in the middle of the ‘boondocks,’ hence the name. One of the two owners said of Capitol Hill, ‘It was on the way down,’ but that he was good at ‘sensing trends’ and that after a demographic study of the area they decided it was on the verge of rejuvenation, which would result in the restaurant’s success. ‘The study showed that the white population would come back. And that’s what happened. Professionals, singles, young marrieds [sic].‘”

While this was taking place along the Broadway strip, something more sinister was happening on the other side of the hill near 23rd, in what was then called East Capitol Hill. In the same report, a person identified only as “an elderly black woman” from the Central District explains:

“They gave me a hard time when I tried to move in around here in 1963. Every rooming house turned me down, some even asking if I was a prostitute! Finally I decided to build my own place, and they gave me a hard time downtown with the permit. I ran into a lot of resistance because of my color. The real estate agents are paying to have houses burned down. All my neighbors have been offered enormous sums of money to sell. The whites want this place, but I’ll be damned if they’re going to get it!”

The process of gentrifying the Central district is still underway, although it has met with resistance over the decades. Ever since the rebellion in 1968, there has been an effort to retain the black and working class character of the neighborhood against the tide of gentrification. However, the government sponsored influx of drugs and gangs starting in the 1970′s has severely damaged the Central District and allowed the developers and out-of-town landlords to acquire more property. It also created a justification for racial profiling by the SPD, an organization that has continued to murder, jail, and plant drugs on young black people for decades.

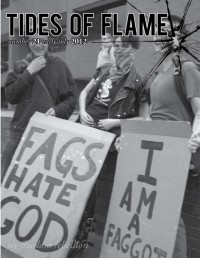

During the last years of the 1970′s, two SPD officers led a campaign to repeal a city ordinance that protected gay rights. The group these cops formed was called SOME, or Save Our Moral Ethics. On Capitol Hill, the radical gay community mobilized against this initiative and in the process revealed some new truths about the neighborhood: firstly, that throughout the decade the gay population had exploded; secondly, many gay people were conservative and just wanted to live a normal capitalist life, in contrast to the radical gays of the neighborhood who wanted to subvert it. The same report quoted above goes on to say:

“Every week or so new graffiti appears on walls on Capitol Hill, sometimes the slogans suggesting it was written by radical lesbians. The pro-gay graffiti is more a sign of efforts to gain a political footing rather than a reflection of actual dominance. The radical gay community on Capitol Hill is numerically small, yet vocal and politically potent. Some of the recent graffiti demands—in no uncertain terms—that the rich leave Capitol Hill immediately, and demonstrates in a graphic fashion growing class conflict in the community. On the other hand, I also interviewed gays who were financially secure and bothered by the growing anti-development sentiment.”

In the 1990′s and 2000′s, the conservative, mainstream gay population began buying and renting property in the Central District, creating more conflict in their wake. Today, the gay identity has been absorbed into capitalism rather than continue to be excluded from. The 1970′s was a time of emancipation and coming out, but it was also a time of mainstreaming and the beginning of the gentrification that continues to this day.

Conclusion

1968 was a year of uprisings across the planet. France, Italy, the US, Mexico, Japan, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Poland, and Brazil were all host to rebellions against the established order. It was the beginning of a period of struggle that would last for nearly a decade and engulf the planet. Some call this time period the Cold War, others call it World War III, and still others call it simply the revolution. It was a global battle that swept up two generations in its complexities and day dreams. Ultimately, the battle was between the USA and the USSR, between state capitalism and state capitalism, but within the cracks of these monolithic entities life was able to blossom.

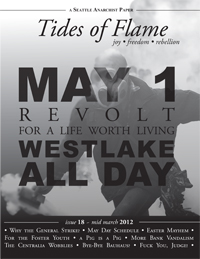

Two years have elapsed since the Occupy movement arrived in Seattle and it was just a few months ago that police gassed hundreds of people downtown during May Day, 2013. Another network has started to form in Seattle that is just as rhizomatic, nuanced, and informal as the last one. It carries the flame of rebellion within it, raw and new, gathering momentum, constantly growing. Repression has recently swept through the city in various forms and yet the network persists. There is an entire history of struggle to look back on and learn from. This article was written as a contribution to the transmission of those old lessons and a reminder to not repeat mistakes that have already happened.

Leave a Comment

Filed under Uncategorized